- Home

- Richie Narvaez

Hipster Death Rattle Page 8

Hipster Death Rattle Read online

Page 8

But once Steven was in the elevator, the image of the dead man and the machete man jumped into his mind again. He tried to think of something else and then remembered: the cupcake! But he was not going back out there now. No way. Erin would just have to deal with not having a cupcake. She would just have to.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Adam Horvath hailed from a small town called Atlantic in Iowa. He had been raised with fresh air in his lungs and trees, regal and green, on every horizon. He had moved to Billyburg years before, following a swarm of almost two dozen of his peeps from the University of Michigan, happy to be in a city bloated with excitement and money, opportunity and money, and sex and money. But too, too quickly, over just his first summer, he had come to hate the hot, stanking city. How the mosquitoes and the roaches and the fat, green bottle flies seemed to be everywhere, and how during heat waves, the garbage outside restaurants turned sour, chemicals bubbled up through the blacktop smelling like rotten eggs, and what was that funk coming from Newtown Creek?

It got worse every summer, and every summer he considered moving to Colorado, L.A., even San Francisco, or, if every drop of his luck—and his trust fund—dried up, back to the fir-lined roads of Iowa.

He wobbled on crutches along Kent Avenue, just off of North 1st Street, toward the Schaefer Landing, a condo development built on the site of the old beer factory, right on the waterfront. He had busted his foot at McCarren Park Pool the week before.

A stupid show-off dive it was, just to impress Katie, the hottie project manager at his job. They hung out all the time, even though she had a boyfriend. The dive must have looked good, maybe even graceful. But then he bounced off of some obese black dude and did a wild somersault, smacking his right foot into the pool edge. Three out of five metatarsals snapped.

It was past midnight and still hot. Flies everywhere. He could feel the crutch saddle fermenting a swamp in his left armpit. And he was drunk, too, very drunk, after celebrating—in the middle of the week—the launch of a new ad campaign he had pitched and helped design—all while in a cast! Katie had been there at the bar, egging him on to do one more Irish Car Bomb, looking incredible in a supertight Wonder Woman T-shirt, her hands stroking the wood of his crutches. Her boyfriend gave him dirty looks the whole time, made snarky comments. Too bad for you, bro.

Then they finally left, the boyfriend’s patience ended, and he dragged a drunk Katie out of there. “See you, Monday,” she’d said, wink-winking.

Monday, sure, yeah, yeah, and maybe after a few more late nights with the gang from work and maybe once, maybe twice alone he’d be able to tap that, take her back to his condo, impress her with his uniquely spacious layout and private balcony with a view to die for. That boyfriend of hers was way too much of a douche. She deserved better. At least for a little while.

He was looking forward to getting some zzzzs when some dude on a bicycle buzzed him, knocking one of his crutches away, almost pushing him to the ground.

“What the f—?” Horvath said, wobbling. He leaned heavily on his other crutch. In his liquor-lined brain, he grasped that he might possibly be in trouble, and then the first slash came. No way this was happening. The dude had gotten off his bike. In his hand, he had—Holy shit! Was that a machete? Oh no! Like in the news feed!

The dude raised the blade.

“Shit!” Horvath said. He threw a crutch sideways and it landed right back next to him. “Fuck off, man. You’re not getting any of my shit. Fuck off!”

The biker came close and whispered, “Die, yuppie scum.” And then he brought the machete down hard. Like a butcher on a particularly stubborn bone.

Horvath thought that he couldn’t die, that this wasn’t his time. His parents would be crushed. He would never see his mom again. He would never ever get to tap Katie, the hottie project manager. He listened to the spokes of the bicycle ticking away. He listened to fat bottle flies buzzing around his face.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Tony’s iPhone rang from way down at the bottom of a dream. He cracked an eye open and reached for his phone, dropped it on the floor, cursed, then picked it up again.

“What?” he said.

“Tony? Hi, it’s Ken Stoller. Patrick’s dad. I hope it’s not too early.”

Tony checked the time. It was just past 8 a.m. “Yeah, no worries.”

“Sorry to trouble you,” Stoller said. “But, you see, we got through at the station yesterday and so decided to get on back home today. We’ve been staying at Patrick’s place and packing things up, but we got to get them downstairs and to our car, try to fit as much as we can in there, though I don’t know how.”

“Uh huh.”

“We were hoping,” he said, “well, we’d love for you to come by and help us out if you could. You did say ‘Maybe.’ And we’d really love to meet you, too.”

“Right now, you mean?”

Tony had planned to get freelance work done and then swing by the park for a few rounds of pétanque. He was about to say he wouldn’t have the time. But he realized they had just spent a lovely visit to New York seeing their dead son and then spending the night in their dead son’s apartment.

“Yeah,” Tony said. “I guess I can come by.”

“Terrific.”

An hour later, Tony walked up to Patrick’s apartment building on South 3rd and Havemeyer. Like many of the older residential buildings in Williamsburg, this was a row house, but it had miraculously escaped the false promise of aluminum siding, or siding of any kind, and so its dark red bricks were exposed, looking scruffy and in need of mortar. A warped awning above the front door matched the bricks perfectly, as did the few shattered steps of the front stoop.

Parked in front was a mud-dirty SUV with a Pennsylvania license plate. An older man came out of the building holding a food processor (sleek) and an albino armadillo (stuffed). Following him closely was a sausage-shaped beagle that waddled. The man wore shorts and a polo shirt, topsiders, and had gray hair that was white at the sideburns. Tony recognized his face from the Christmas photo.

“Mr. Stoller?” he said.

“You must be Tony.” The man held out his hand from under the food processor. The sausage dog got between them, nudging Tony like a linebacker. “Meet Major Alphons.”

The beagle looked up at Tony with doleful eyes. “Hey, dog.”

“I was getting worried about you. I called a while ago.”

“I’m more of a late afternoon-slash-early evening person,” Tony said, wincing internally at his word choice.

“I understand. But I’d like to get going early as I can, you know?” Mr. Stoller unlocked the SUV’s side door, put in the box, and locked the door again. “Can’t be too safe.”

Patrick had lived on the top floor, three flights up. The linoleum on the narrow stairs was old and peeling, the banisters loose and rickety.

As they walked up, Ken Stoller said, “You know, I think we almost had a break-in. Someone was trying to come in through the back window, up the fire escape back there. My wife thinks I’m being paranoid, but then I ask her, ‘So why was Major Alphons barking up a storm?’ and he was.”

In the apartment, Patrick’s mother was packing glassware in the kitchen. Ken Stoller introduced her, and she nodded and then turned back to the glassware. She was taller than her husband by a head, with silver hair and a small, hooked nose that made her look like a bird.

As Tony walked into the apartment he noticed one, two, three locks on the door, a hell of a lot of security and more than he remembered being there. The apartment was the railroad style, long, narrow, opening into a kitchen with a new stove and a narrow stainless steel kitchen island. The floor was new, too, tile in the kitchen, parquet in the living room. The off-white paint on the walls had been peeling last time Tony saw them, but now they were a shiny pastel purple. Patrick must have put all his money into renovating.

Tony had only been to Patrick’s place once before, for a New Year’s Eve party. He didn’t want to go, but when he

found himself drinking alone at a bar, he figured he’d just stop by. Big mistake. Everyone at the party was coupled up, and so Tony felt like a thirteenth wheel. The others played video games and nuzzled and teased each other in the small living room, and he hung out in the kitchen by the window, drinking one watery PBR after another. Patrick’s girlfriend, Kirsten, must have caught on. She came over and asked him if he was okay. She had eyes a little too far apart, and a button nose, giving her a passing resemblance to a frog. Still, a very attractive frog.

In lieu of a real answer, he’d said, “You know they used to tie real ribbons around every bottle of Pabst?”

“Was that in the nineties?”

“No, about a hundred years ago.”

“You don’t look that old.”

“Wait till midnight. That’s when I turn into a rotted pumpkin.”

“Oh, I can’t wait till midnight then.”

He stayed for another couple of hours, getting bored and getting drunk. Which took an awful lot of watery PBRs. Just before midnight, when everyone else was due to smash lips together, he slipped out and sulked home, keeping his rotted pumpkin face to himself.

Well, that was a lousy memory. The living room, just off the kitchen, held a mix of IKEA furniture and old stuff that looked like it had been found on the street. On one side, posters covered the walls—Mean Streets, The Warriors, A Clockwork Orange (in velvet), and one of a concert for some band or someone called Manu Dibango. On the other side, over what looked like a brand new couch, were three framed paintings of dogs playing poker.

In the kitchen, Sarah said, “All this stuff is good,” holding an aluminum pot and some utensils. “We should save it.”

“We don’t need it. And we’re going to run out of room in the car,” said Ken. “Tony, do you need any of this stuff?”

Tony didn’t like the idea of taking a dead man’s things. It was too close to grave-robbing. “Thanks,” he said, “I have all the kitchen stuff I need.”

“Well, do you know a place where we can donate this?”

Before Tony could answer, Sarah shot back, “But we should take these home.”

“I tell you, there’s just not going to be room in the car for all this stuff,” Ken said.

“You’re not doing that right,” she said. “You don’t know how to pack.”

“Of course I know how to pack.”

“Did you find his big suitcase? We could put things in his suitcase? I don’t know where anything is. How am I supposed to pack everything?” she said, and then her eyes watered, and she turned and went into the only place you could get privacy in a railroad apartment—the bathroom.

Ken Stoller looked at Tony and then began picking up a box. Tony turned and did the same with a surprisingly heavy box in front of him. Vinyl record albums. He put it down and looked for something lighter. But the next box was packed with books. Hardcover books.

Over the next few hours, going up and down three flights of stairs, Tony debated which was more lethal to his back, milk crates of vinyl or boxes of hardcovers. He lost interest in the debate when he saw how stoically Ken was handling the burden of crates. Still, if Tony had to guess, the vinyl was the worst.

On the fifth trip back up, Tony saw a woman on the landing talking to Ken. She was one of those genetically gifted people (unusual height, skeletal limbs, high cheekbones) who were destined to be models. Or destined to be constantly told they should be models. She wore shades, a backward baseball cap, and shorts short enough to embarrass a gynecologist. Tony was making a half-hearted attempt not to notice this when he saw that the door next door to Patrick’s was open. This woman must live there, must have been his neighbor, and then Tony realized that apartment next door used to be Rosa Irizarry’s. As Tony approached the landing, the model turned from Ken and was closing the door, but Tony got a quick glimpse inside. Bright colors, new fixtures. It looked like whatever was left of Rosa Irizarry had been renovated out of existence.

Once the car was packed, Tony sat on the stoop sucking down a bottle of water Sarah had handed him. Ken sat next to him and handed him a small cardboard box.

“Got you a present.”

“A present?”

“Not from me. Found this bag with your name on it. Patrick must have wanted you to have it.” It was a small ziplock bag with several flash drives in it. “Matter of fact, there’s a whole bunch of this stuff we for sure don’t need. We’re not techie people. You take it. Looks like stuff you could use as a reporter.”

Tony was too tired to resist. In it were several mini-webcams, a dozen or more sealed baggies of flash drives, and operating system CDs in their original sleeves. He took the plastic baggie and the box but planned on tossing it all into the first garbage can he came across.

“I found a bunch of those little memory sticks all over the apartment,” Ken said. “In the couch, in the medicine cabinet, in his shoes. I bet he must have been sore looking for where he lost them.”

Tony found the strength to say, “Thanks.”

The Stollers invited Tony down to Pennsylvania for the funeral, but he told them to let him know and he’d see.

“Reporters,” Ken said. “Always working.” Then he bent down to give Tony an awkward hug. It would have been awkward regardless of the angle. And it didn’t help that Tony was covered in sweat and very aware of it. Sarah just shook his hand.

“You can come down to Allentown any time you want,” Ken said. “You’re like family now.”

They drove slowly away, leaving Tony on the stoop next to a few black garbage bags filled with the rest of Patrick’s possessions that didn’t fit in the car. Including a couch. It was a good-looking couch. But Tony wasn’t going to try to move it. It wouldn’t fit in his apartment anyway.

He was in no shape to play pétanque, not that pétanque required much in the way of shape. He walked over to the Sentinel.

When Tony got there, Bobbert was in his office, talking to someone on his cell phone. When he saw Tony, he yelled him over.

Bobbert Swiatowski was a doughy man in his late fifties who unwisely wore a goatee and kept it and what was left of his hair dyed jet black. He was, as usual, in shirtsleeves with the sleeves rolled out to show off meaty forearms. Bobbert’s office was well air-conditioned, but he was still shiny with sweat.

“Sit down, sit down, sit down,” Bobbert indicated the guest chair at the side of his desk. It was covered with stacks of the latest issue—the last one Patrick finished, Tony realized.

“Hey, Tony. Hey, listen, how you holding up?” Bobbert said. He held his hand over his cell phone.

Behind him on a corkboard were well over a hundred printed pictures of Bobbert’s family: wife, four kids, two dogs, and two cats.

“You want to finish that call?” Tony said.

“That’s okay,” he said, holding the phone askew and whispering. “This is Maru, telling me about her adventures with her Bear Bear. You want to say hi?”

“Not at the moment.”

“I understand. I can only understand every third word she says.” Into the phone, Bobbert said in a high-pitched voice, “And his teeth were BIG?” Then, in a normal voice, he said to Tony, “My wife’ll kill me if I don’t invite you over this weekend. She’s making pork knuckles.”

“I love her pork knuckles.”

“She knows. She knows. Tell me about the TIGER!”

“I’ll have to see.”

“Here, Maru wants to talk to you. She heard your voice.”

Tony got on the phone and listened to the child’s incoherent story for what he felt was a respectable amount of time.

“I guess I ru ru you, too,” Tony said, handing back the phone.

“You love kids.”

“I hate kids.”

“You love my kids. Bye bye, Ruru, Daddy has to get back to work.” After some more back and forth with his daughter, Bobbert kept the phone by his head and said, “Listen, so I want to talk about your future here at the Sentinel.”

“Maru’s still on the phone?”

“Yeah, she’s still on the phone. It’s about Bear Bear’s favorite ice cream now.”

“Well, my future is my present,” Tony whispered back. “That’s the way I—”

“Sure, sure, but with Patrick gone, well, you know, we need you to do more. And to be honest, you know and I know that you could do more. You have the talent.”

“But not the patience. And I’d have to be here every day.” And no more waking up whenever he wanted, he thought. And no more long afternoons in the park.

“I’ll give you Patrick’s salary.” To the phone, Bobbert said, “That’s terrific, sweetheart. Bear Bear taught you to fly.”

“Can I ask what Patrick was making?”

“Twenty-eight K.”

“Twenty-eight?” Tony thought of Patrick’s apartment and all the new furniture and fancy kitchen gadgets he had. “Patrick was only making twenty-eight?”

“Hey, I’m not lying,” Bobbert said. “Twenty-eight K. I might be able to get you more, but, honestly, things have been touch and go lately.”

It was just a little more than what Tony was making now, scraping by. But if he could still do other freelance work at the same time, he could almost be respectable. “Can I think about it?”

“Why are you crying, honey? Tell Daddy what’s wrong,” Bobbert said to his phone. “Yeah, Tony, but you gotta tell me soon, or, honestly, then I gotta start looking elsewhere.”

Tony walked the two feet over to the writers’ office and could still hear Bobbert talking on the phone. “Don’t cry, honey. Bear Bear is not flying away.”

Gabby was at her desk, hair pulled back and wearing a thin tank top and tiny terry cloth shorts that Tony made an effort not to notice.

“Ew. Did you not shower today?” Gabby said.

Hipster Death Rattle

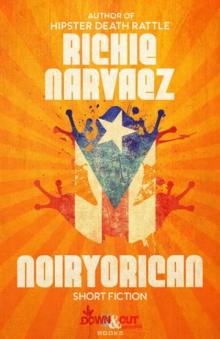

Hipster Death Rattle Noiryorican

Noiryorican